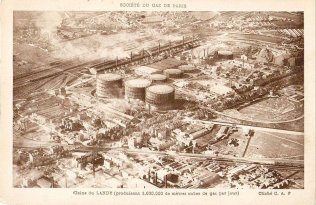

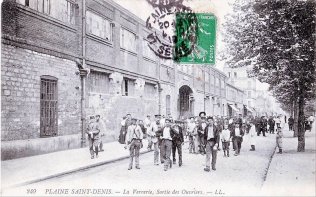

At the end of the 19th century, La Plaine-saint-Denis experiences an important industrial development. The neighborhood is built around large factories and provincial or international migrants are ready to work in terrible conditions and to live close to the factories. As Bretons did before them, Spaniards settle at the end of the 19th century in the “quartier des passages” in La Plaine, renamed the Little Spain.

At the end of the 19th century, La Plaine-saint-Denis experiences an important industrial development. The neighborhood is built around large factories and provincial or international migrants are ready to work in terrible conditions and to live close to the factories. As Bretons did before them, Spaniards settle at the end of the 19th century in the “quartier des passages” in La Plaine, renamed the Little Spain.

In 1911, 260 Spaniards live in Saint-Denis, especially in the Plaine neighborhood: 145 live avenue de Paris (now avenue du Président-Wilson), and others settle rue de la Monjoie. Rue de la Justice, which will become the heart of the Spanish neighborhood after 1918, only welcomes four families coming from Spain.

In 1911, 260 Spaniards live in Saint-Denis, especially in the Plaine neighborhood: 145 live avenue de Paris (now avenue du Président-Wilson), and others settle rue de la Monjoie. Rue de la Justice, which will become the heart of the Spanish neighborhood after 1918, only welcomes four families coming from Spain.

The community is composed of 70% of men (including children). This situation is due to the numerous Spanish homes hosting “cousins”, “relatives” and other “guests” (mainly very young) employed by the Legras glass factory. It is, in fact, a trafficking of young people from 11 to 19 years old, hired in small villages of the province of Burgos, one of the poorest countries of Castile, by some slave traders coming from the same region. In 1940, more than 40% of Spaniards living in Saint-Denis come from this province. After being hired by the Legras glass factory, these “intermediaries” who also work for the factory, get a large part of the children’s salary. The young boys, mainly laborers, are only paid at the end of the year to avoid any escape from them. They live in the same house than their “sponsor” and his wife, with no privacy.

More than 50 young boys, with an average age of 15 ½ years old, live in these conditions in 1911. In La Plaine, next to Aubervilliers, 137 Spaniards are also victims of this situation.

Three major Spanish immigration waves hit the cities of Saint-Denis, Saint-Ouen and Aubervilliers in the 20th century. First, “economic” migrants settle in the 1920-1930’s. Then, some political migrants settle between 1939 and 1950 after the Asturian miners' strike of 1934 and the defeat of the Republican Party in 1939. Finally, other economic migrants settle between 1955 and 1970.

According to the 1931 census, 8,500 Spaniards live in these three cities and France counts a total of 189,600 Spanish inhabitants (4,5%), making them the first foreign community of France, way ahead Italians.

Yet, the 1930’s crisis and the important unemployment push the Spaniards to go back to their country. While Aubervilliers welcomes the largest community of Spaniards with 4,348 inhabitants in 1931, they are 2,269 left in 1936. Some of them go back to Spain, other leave Aubervilliers to settle in Saint-Denis to take advantage of unemployment benefits given to immigrants by Jacques Doriot, mayor of Saint-Denis (for a three month stay in the city at least) whereas Pierre Laval, mayor of Aubervilliers, refuses to provide any allowance.

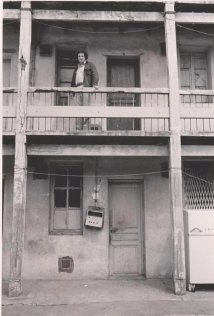

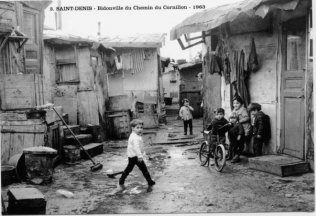

Delimited by the avenue du Président-Wilson on the west side (former avenue de Paris), the Canal Saint-Denis on the east side, the rue du Cornillon on the north side and the rue du Landy on the south side, the Little Spain is a maze of narrow streets, built up by Spanish laborers who settle their houses on this formerly vacant site.

Delimited by the avenue du Président-Wilson on the west side (former avenue de Paris), the Canal Saint-Denis on the east side, the rue du Cornillon on the north side and the rue du Landy on the south side, the Little Spain is a maze of narrow streets, built up by Spanish laborers who settle their houses on this formerly vacant site.

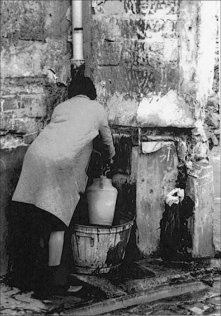

The “quartier des passages” does not have access to electricity, gaz, water and mains drainage until the fifties. Inhabitants have to supply water from the fountain-posts located at the corner of rue du Landy and rue de la Justice.

The French inhabitants do not like this migration. Some of them do not hesitate to send letters (anonymously or not) to the city hall or even to the police headquarters. The press gets involved in the situation denouncing promiscuity, too large families, lack of hygiene and violence.

Yet, during the same period of time, La Plaine police station attests that the Spanish population is rather quiet, with only a few conflicts within the community or with the French and Italian communities.

Yet, during the same period of time, La Plaine police station attests that the Spanish population is rather quiet, with only a few conflicts within the community or with the French and Italian communities.

The Spanish community creates a true link between its inhabitants. With chairs and tables on the sidewalks, people play dominos while children play in the streets. Spaniards are united and celebrate Easter, Christmas, New Year’s Eve or Labor Day all together.

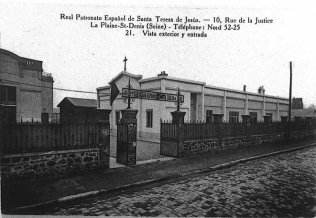

Since Alphonse XIII (King of Spain from 1886 to 1931), the French or Spanish socialist press denounces the barbaric life conditions of the immigrants: “spectral landscape, foul smell, promiscuity and unsanitary homes subject to fires”. In 1913, the king sends one of his chaplains, Mgr Palmer, member of the Congregation of the Claretians, to solve the problem. Mgr Palmer buys a land to build a church, rue de la Justice in La Plaine, in the heart of Little Spain. After the First World War, a rich Mexican patron (or a Parisian lady possibly), gives the money to build the Saint-Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus Chapel (June 1923) and the support of the Hogar (1926). Migrants, mostly coming from the street, are extremely religious and are frequent visitors: on every Sunday, the Mass gathers more than 200 persons. Claretian Fathers celebrate baptisms, confirmations, weddings, funerals but also provide social assistance. A concert hall and a free clinic addressed to Spanish immigrants are built on the same land.

Yet, El Hogar de los Espanoles is not a success among Spanish laborers because most of them are dechristianized. The situation gets worse when the civils servants of the Patronato choose the nationalist party in 1936. The Falangists take over control the Spanish Hogar and, even if they are in minority, the place becomes a representative of Francoism until the end of the dictatorship.

Yet, El Hogar de los Espanoles is not a success among Spanish laborers because most of them are dechristianized. The situation gets worse when the civils servants of the Patronato choose the nationalist party in 1936. The Falangists take over control the Spanish Hogar and, even if they are in minority, the place becomes a representative of Francoism until the end of the dictatorship.

Today, the Hogar de les Espanoles is still visited by Spaniards from La Plaine or elsewhere. Located at 10 rue Cristino Garcia, this establishment is open on every weekend and members of the association can attend concerts, plays, exhibition and take dance or guitar lessons. The restaurant and tapas bar, both still vibrant places, preserve the Spanish culture.

The Spanish civil war and the Second World War turned the life of the Little Spain in La Plaine upside down. Since the beginning of the civil war in July 1936, Spaniards wonder if they need to go to fight. A large majority of the community aligns with the Republic and keeps away from priests of the parish, who pledge allegiance to the nationalists. Around forty Spanish men, from 18 to 46 years old, go fight for the republican party. The other ones staying organize a support network for communists or anarchists. They actively participate in solidarity with the republican Spain and families of the men gone to fight: meetings, tools and equipment collections on the public highway, movie projections… After Francisco Franco’s victory in 1939, families from Little Spain come together to adopt orphans or refugees from the republican army and, during the occupation, several Spaniards participate to the resistance.

In September 1941, an important raid, organized by the French police and the Gestapo, leads to the arrest of numerous members of the resistance. After closing off the neighborhood, German soldiers search hotels and buildings. 11 Spaniards ad five French members of the communist party are arrested and killed or deported. The active participation of the Spaniards to the resistance helped for their integration after the war.

After WWII, several families of political refugees settle in Aubervilliers and Saint-Denis because of the important presence of communists. After many escapes Fidel Fernandez (alias Ordonnez), his wife Mathilde and her parents, the Recatala family, settle in La Plaine-Saint-Denis in 1946. Their son, the writer Denis Fernandez-Recatala, is only a few months old. They found a house at 3 passage Boise. Fidel quickly finds a job as a painter and Mathilde as a “trieuse de chiffons”.

After WWII, several families of political refugees settle in Aubervilliers and Saint-Denis because of the important presence of communists. After many escapes Fidel Fernandez (alias Ordonnez), his wife Mathilde and her parents, the Recatala family, settle in La Plaine-Saint-Denis in 1946. Their son, the writer Denis Fernandez-Recatala, is only a few months old. They found a house at 3 passage Boise. Fidel quickly finds a job as a painter and Mathilde as a “trieuse de chiffons”.

Refugees also move to La Plaine after crossing the Pyrenees to escape the Francoist Repression. A governmental ban forbids them to settle in the Seine department. Some of the Spaniards who had already lived in La Plaine or have a family there succeed in crossing the border. This was the case for François Asensi’s family, the actual MP and mayor of Tremblay-en-France. After a few arrests and imprisonments, his father Paco who left La Plaine to fight is Spain and his wife Nina who join them, come back as illegal immigrants with their two children, Sonia and François in 1947.

After the WWII, members of the second generation start leaving La Plaine. Despite a neighborhood closed to strangers and parents withdrawn into themselves, children integration is going well. They even get married with French inhabitants. They first go to school, entertain themselves (balls), and go to the factory and to the communist party committee where Spaniards and French meet each other.

After the WWII, members of the second generation start leaving La Plaine. Despite a neighborhood closed to strangers and parents withdrawn into themselves, children integration is going well. They even get married with French inhabitants. They first go to school, entertain themselves (balls), and go to the factory and to the communist party committee where Spaniards and French meet each other.

They move in social housing or detached houses, meaning that they succeeded. The arrival of numerous republican exiled people (Spaniards deported in Germany for example) replaces the ones leaving.

Because there are not enough accommodations inside the Little Spain, illegal houses are built up around the neighborhood. Some of them will be partly destroyed at the beginning of the seventies.

On the other side, La Plaine welcomes new peoples. Spaniards leave the city and are first replaced by Algerians and Portuguese coming for the construction of the A1 highway and social housing projects. At the end of the 50’s, these laborers live per dozens in small apartments where Spanish families used to live. Both Algerians and Portuguese get along with each other, leading to intercommunity marriages.

On the other side, La Plaine welcomes new peoples. Spaniards leave the city and are first replaced by Algerians and Portuguese coming for the construction of the A1 highway and social housing projects. At the end of the 50’s, these laborers live per dozens in small apartments where Spanish families used to live. Both Algerians and Portuguese get along with each other, leading to intercommunity marriages.

From the 2000’s, new migrants are coming from all over the world. Cape Verdean replaced the Portuguese next to Aubervilliers. Sri Lankan, Bengali, Malian and Asian people moved in precarious accommodations in the rue Cristino Garcia. With the construction of the Stade de France and new private apartments, the old Spanish hovels and brownfields are destroyed.

Learn more about with our cultural tours in Paris.