The Paris population and its suburbs is the result of a successive wave of immigration from both home and abroad, from the Middle Ages up to now. Since the 19th and 20th century, the labour market brought immigrants to Paris and its suburbs. Portuguese, Spanish and Italian between the two world wars. Portuguese and North African between the 1950s and 70s, Sephardic jews after independance from North African countries, and Sub-Saharian Africa and Asia since then. See our multicultural tours of Paris offers: Discover traditional food and art!

The Paris population and its suburbs is the result of a successive wave of immigration from both home and abroad, from the Middle Ages up to now. Since the 19th and 20th century, the labour market brought immigrants to Paris and its suburbs. Portuguese, Spanish and Italian between the two world wars. Portuguese and North African between the 1950s and 70s, Sephardic jews after independance from North African countries, and Sub-Saharian Africa and Asia since then. See our multicultural tours of Paris offers: Discover traditional food and art!

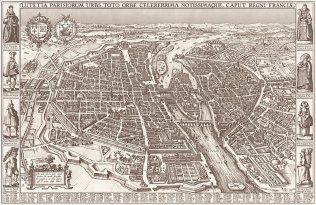

Medieval Paris was one that automatically formed groups of affinity. It is therfore not surprising that certain artisans or shopkeepers gave their name to the street they worked on: gunsmiths, grocers, skinners, cobblers, coopers, washerwomen, butchers all have their street name. Religious orders, orthodox, jewish, and migrants from the different provinces also tried to group together. Migrants from Brittany, Normandy, Flanders or Picardy lived together on the streets of their name. Italian merchants and bankers also had their own, « la rue des lombards » - from the region of Lombardy in Italy.

Regarding the different trades, this phenomenon can be explained, on the one hand, because of the strict control by the Guilds and on the other by the greater ease of use and operation. It was possible, for example, to share certain tools or equipment in common. The main reason being of course, solidarity, as much for the cobblers as for the Bretons seen as how they were neighbours. The arrival of migrants from Brittany or Normandy adapt even more easily as they come from a "country" or "region". This can still be seen today.

It was during the 13th century that the Italian bankers, the lombards, who at that time used to attend the Champagne fairs, settled in Paris. People from Siena, Florence and Lucca were already quite numerous by the end of the reign of Louis IX, future Saint-Louis (1214-1270). Under Philippe le Bel (1268-1314), we could find them in close quarters near Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie (now Saint-Jacques tower), the churches Saint-Merri and Saint-Opportune and areas around les Halles. The Italian lombards, like the future jewish lombards, had to put up with waves of zenophobia which became apparent at each social movement.

In the second half of the 15th century, strong economic recovery of activities within the capital attracted many foreigners to Paris. The Germans, Flemish, Brabançons and Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese arrived. With the development of the printing press first owing to the Rhine states, whole German dynasties were attracted. The following century, areas developed and, towards 1520, there were no longer any lombards on the streets carrying this name but confectioners! At this time, Spanish, Italians, English and Germans were firmly settled and it was from this date on that Paris became a true cosmopolitan city.

For a long time, it was Parisian usage to Frenchify foreign names. Everyone stood to gain from this, even more so the person concerned, for it was in his interests to integrate into society with a name that the neighbours could pronounce. Wars sometimes made these « new Parisians » feel ill-at-ease. This was the case during the time of Louis XIV where it was not good to be the subject of a monarch at war with the Sun-King.

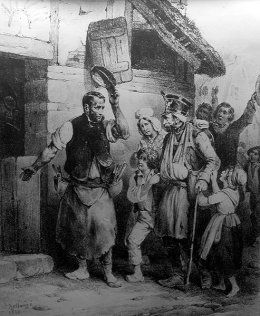

French provinces were met with a financial crises during the 1850s. This crises was particularly bad in regions where home industry took place, for example to the East of the Paris Basin that provided Paris with a large number of migrants. Workers on the home soil were not the only ones hit and agricultural wages, even with their disparities, only allowed for the minimum of living conditions. Paris thus became a popular spot for the rural population in need of a new place to live. Furthermore, changes brought about by the transport revolution reduced isolation of the provinces but at the same time also unsettled the former stability of the French countryside by allowing for easy movement.

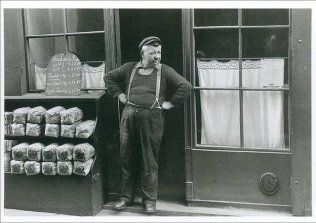

Hardship forced the rural population to leave and Paris acquired, over fifteen years, from 1851 to 1866, 300,000 people in search of stability that their village could no longer provide. But someone coming from the countryside who might not speak French would find it difficult to integrate not understanding the way of life here and the social discipline. In some areas, workers continued to group together according to trade, without direct liaison with their place of origin. This is the case for example, for carpenters or ironworkers in the Picpus district or the laundries in the Goutte d’Or district. However, other migrants grouped together by place of origin such as bricklayers from the Creuse, Auvergnat water carriers or Breton domestic staff. These last two types of migrants had particularly chartacterised Paris and area around.

Hardship forced the rural population to leave and Paris acquired, over fifteen years, from 1851 to 1866, 300,000 people in search of stability that their village could no longer provide. But someone coming from the countryside who might not speak French would find it difficult to integrate not understanding the way of life here and the social discipline. In some areas, workers continued to group together according to trade, without direct liaison with their place of origin. This is the case for example, for carpenters or ironworkers in the Picpus district or the laundries in the Goutte d’Or district. However, other migrants grouped together by place of origin such as bricklayers from the Creuse, Auvergnat water carriers or Breton domestic staff. These last two types of migrants had particularly chartacterised Paris and area around.

We can find evidence of a Breton influence in Paris from the Middle Ages. At the end of the 19th century and with the completion of the Paris-Brest railway line, thousands of Bretons tried their luck in the capital. Arriving at the Gare Montparnasse, many among them did not dare venture any further and settled here. The Bretons recreated a genuine little Brittany in the 14th district. Lacking instruction and generally speaking Breton only, these new arrivals were a welcome source of workmanship for the most arduous work. Women were the most to leave and found themselves as maids, nannies or concierges. Others, not so lucky, found themselves on the streets of the capital. This phenomenon became so widespread that welcome committees were set up to prevent pimps from picking girls up the second they stepped off the train at gare Montparnasse.

In 1883, the number of Bretons in the capital had already reached 12,000 and they began to settle further afield outside of the capital and around. Bretons came to Saint-Denis during the 1890s when la Plaine and pleyel districts had begun to become industrialised. As for people from Auvergne, they began to arrive in Paris from 1750. They were at first water carriers or ironworkers and made the Bastille area their home – an « Auvergnat village » in Paris. Here they opened cafés known as the « bois-charbon » - wood and coal, the famous « bougnats » - immigrants from the Auvergne region, including the first dance-halls where one could dance the bourrée or borry dance to the sound of the Auvergne-style bagpipes that mingled with the sound of the Italian diatonic accordeon.

Comprising engineers and qualified workers, English emigration became established in France from the Restoration (1814-1830) up to the Second Empire (1852-1860). Thanks to their savoir-faire and the fact that they had their industrial revolution before France, the British distinguished themselves in the fields of iron and steel and were founders of the modern steel industry. About 80,000 English previously trained technicians crossed the English Channel thus enabling France to launch its metal industry and build its first railways. These immigrants sent rent prices rocketing in Faubourg Saint-Antoine where they settled. The « Great Emigration » of the Polish people, which is how it was known then (and still is today), represents the most important of political exiles of the 19th century from 1830 to 1870. After the failure of the Warsaw revolution against Tsarist power (1830-1831), the insurgent leaders took refuge in Paris and formed base in Ile Saint-Louis where they held genuine court with, at its head, Prince Adam Georges Czartoryski. Others joined up with them, notably the poet Adam Mickiewicz and the composer Frédéric Chopin.

Comprising engineers and qualified workers, English emigration became established in France from the Restoration (1814-1830) up to the Second Empire (1852-1860). Thanks to their savoir-faire and the fact that they had their industrial revolution before France, the British distinguished themselves in the fields of iron and steel and were founders of the modern steel industry. About 80,000 English previously trained technicians crossed the English Channel thus enabling France to launch its metal industry and build its first railways. These immigrants sent rent prices rocketing in Faubourg Saint-Antoine where they settled. The « Great Emigration » of the Polish people, which is how it was known then (and still is today), represents the most important of political exiles of the 19th century from 1830 to 1870. After the failure of the Warsaw revolution against Tsarist power (1830-1831), the insurgent leaders took refuge in Paris and formed base in Ile Saint-Louis where they held genuine court with, at its head, Prince Adam Georges Czartoryski. Others joined up with them, notably the poet Adam Mickiewicz and the composer Frédéric Chopin.

Right up to the beginning of the 19th century, the wave of immigrants brought with it bourgeois and well-to-do migrants. After 1835, a wave of immigrant workers brought to Paris the underprivileged English, Belgian, Dutch and German population. This first wave of poor massive immigration from abroad to Paris began with the arrival of poor German farmers fleeing the agricultural crises. Within intramural Paris and the fortifications built by Thiers in 1845, there were 50,000 foreigners in 1850 and 120,000 in 1866. Willing to accept relatively low salaries, these populations brought on once again zenophobic reactions.

Several other migratory waves followed uninterrupted until the first global conflict: Italians and Central European Jews during the 19th century, Armenian refugees after 1915, the Russians after the 1917 revolution, inhabitants of the colonies during the First World War.

In 1931, immigrants registered in Paris and its suburbs were for the most part Italian, Belgian, Russian and Spaniards. Others were Maghreb, African and Asian who came to replace the soldiers in French factories during the Great War.

Up until the 1920s, there were no real ethnic areas, neither in Paris nor the suburbs. Factors included the concentration of people on the scale of a street or building but the cultural mix continued to dominate on the scale of an area or town with the exception of the few rare settlements in the suburbs such as the Armenian population in Issy-les-Moulineaux or in Alfortville. This concerned also the Jews from the Marais district who were soon to leave the Pletzl to settle elsewhere in the capital. Pletzl means « small square » in yiddish and recalls the Saint Paul area in the 4th district in Paris that, from the end of the 19th century to the 1930s, welcomed jews chased out of Eastern Europe by pogroms and anti-semitism. This jewish quarter seemed to function, at least in the short term, as a way to enter in to the city. Over time, the marked out streets overflowed and spread out into the surrounding areas.

The Italians made up the largest portion of a foreign community in the Paris region where they represented two thirds of the foreign population at the beginning of the 1930s. In Paris, the Italians settled in districts in the North-East and Eastern suburbs in the Paris region, They can be found in all areas of construction : bricklayers, diggers, decorators, plasterers, heating installers, stove fitters, and sometimes minor company heads. Leaving Paris to settle in the suburbs and building a house was a sign of successful insertion in a working-class town. Despite waves of zenophobia in times of crises, the Italian population were never really rejected by the local inhabitants.

In 1926 three-quarters of the Spanish population in the metropole were already settled in the northern suburbs, in poor areas situated close to factories which soon became for some the slums of the 1960s. Little Spain in la Plaine Saint-Denis was made up mostly of a poor Spanish working class, the rest being Italian and French from the South of France. The area was made up of delapitaded housing projects right in the heart of a highly industrialised territory stretching from Saint-Denis, Aubervilliers and Saint-Ouen. Little Spain spread out around the Rateau factory in La Courneuve. Here, a new district was formed making the shacks permanent. Strong family networks brought migrants directly from Spain to these dilapidated dwellings in la Plaine Saint-Denis and la Courneuve which remained until the 1970s.

The number of Portuguese in France rose from 50,000 to more than 700,000 from 1960 to 1970. In 1969 and 1970 alone, about 240,000 Portuguese arrived, most of them illegally. In 1968 there were 500,000 Portuguese in France, half of whom resided in the Paris region

The men were employed in the industrial sector, automobile and building construction. In the Paris region, they made up the workforce that built the ring road, the RER, Montparnasse tower and la Défense. They worked a lot in the hope of earning money as quickly as possible to enable them to return to Portugal and build the « house of their dreams » which would mark their success in the village. A large number of Portuguese women became workers, housemaids, concierges, cleaning ladies, thus replacing the Spanish women workers.

The fall of the authoritarian regime, the 25th April 1974, the end of the colonial wars (1961-1974), the emergence of a democracy in Portugal, Portugal’s accession to the European Union weakened the flow of immigrants. Even though they made up the first foreign community in number, these Portuguese liked to keep to themselves, be part of their own associations and live in Portuguese-only living quarters. They were somewhat ignored by French public opinion, unlike the Algerians who, because of the war (from 1954 to 1962), were very much present in the media and debates.

![]() Cultures around the world continue to colour the Paris metropole today. Several events and visits to the different neighbourhoods are proposed all year long. Go inside a sikh temple, discover Indian and European communities (Croatian…), the little Mali district in Château-Rouge, etc. Numerous guided walking tours and visits of Paris are proposed, consult the calendar.

Cultures around the world continue to colour the Paris metropole today. Several events and visits to the different neighbourhoods are proposed all year long. Go inside a sikh temple, discover Indian and European communities (Croatian…), the little Mali district in Château-Rouge, etc. Numerous guided walking tours and visits of Paris are proposed, consult the calendar.

Dreaming to the rhythm of these journeys is proof that one can meet the other close to home. The "traveller" is invited to take a fresh look on the capital and beyond and make a date with the different cultures that form them. Get the picture of Paris and its suburbs, museums and monuments but also the districts, the taste, the festive moments, the highlights with a Paris cultural tour.